Did you know that Spain was on the brink of being invaded by the United States during the Second World War?

Despite what many people believe, Spain played a significant and decisive role in terms of strategy during the global conflict.

Not only because of its location in southern Europe, guarding the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, but also because of its tungsten mines. Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element that was crucial to the war time industry.

Due to the circumstances of the time, Galicia —a region with an abundance of this mineral— was infiltrated by spies from both sides aiming to stake a claim on as much of this particular material as possible.

With this article, we aim to explain the history of the so-called “Wolfram Crisis”, with which Spain teetered on the brink of being plunged into the Second World War.

What is tungsten used for?

Wolfram, more commonly known as tungsten, is a scarce metal that is located in group 6 of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements.

Its atomic number is 74 and its symbol is W.

Though it is rare, it can be found in the form of oxides or salts in certain minerals.

It is metallic grey in colour and known for its excellent durability and density.

Given that its boiling point is the highest of all the chemical elements —5930º C— it is considered ideal for manufacturing light bulb filaments as it bears incandescence well.

It is also commonly used these days to manufacture resistors for electric furnaces with reducing atmospheres.

Another common application for tungsten is in the manufacture of anodes for X-ray and television tubes, as well as in drills used by dentists (in a tungsten and carbon alloy).

In fact, tungsten carbide is a very popular alloy that is used in both high-speed cutting tools and in anti-radiation shields thanks to its excellent resistance against particle emissions, including gamma rays.

Fluorescent tubes also use tungsten alloys with other materials such as calcium and magnesium.

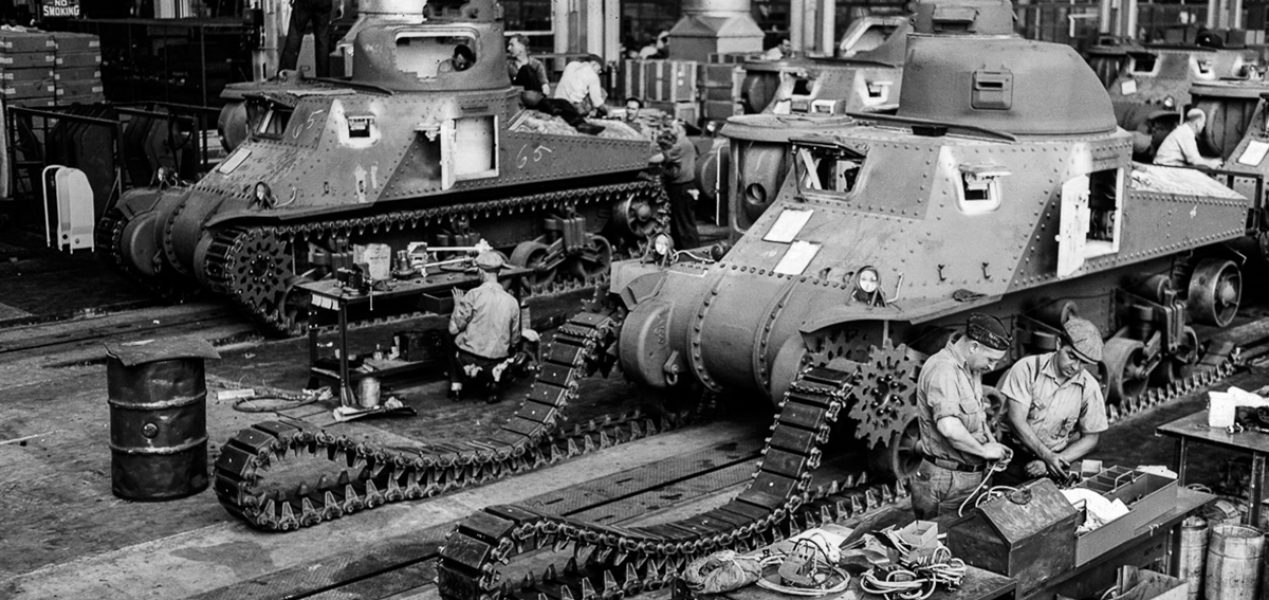

However, without a doubt, its excellent hardness and density have made it a strategic chemical element for manufacturing the most durable types of steel, such as those used in armoured fighting vehicles.

The Nazis and tungsten

Last century, during the 1930s and prior to the onset of the Second World War, the major world powers started stockpiling tungsten as an essential raw material for the manufacture of not only armoured vehicles, but also anti-tank warheads and explosive grenades (tungsten is so hard it can penetrate armour-plating).

The problem was that Germany has no tungsten mines, so the Nazi war industry had to look to other countries that did have access to the mineral, for example China, India, or Myanmar (formerly Burma).

On the other side, the United States did have its own tungsten mines within U.S. territory. What’s more, it could also easily import the mineral from countries like Bolivia, Argentina, or Peru.

The need for tungsten became even more pressing when Germany went to war with the United Kingdom, which effectively blocked trade of the mineral from India or Myanmar.

Later, when the Soviet Union joined the war, the Nazis stopped receiving tungsten mined in China as the mineral could no longer be transported via the Trans-Siberian Railway to Germany.

Therefore, Hitler’s gaze shifted to the Spanish tungsten mines.

Spanish tungsten

During the Spanish Civil War, the aid that Hitler lent to Franco was crucial to Franco’s victory.

But that wartime collaboration didn’t come without a price.

In exchange, the Nazis requested that Franco give them access to the tungsten mines in the region of Galicia.

General Franco —who, despite having declared neutrality, didn’t hide his sympathetic leanings towards Nazi Germany— accepted the deal which would bring wealth and employment to the Galician region.

In fact, the large-scale purchases of the mineral caused its price to skyrocket because the Germans depended exclusively on Galician tungsten to be able to continue manufacturing fighting vehicles and anti-tank warheads.

Mines such as those in Carballo or Monte Neme started operating at full capacity.

In fact, demand was so high that other mining valleys in Cáceres and the Bierzo area of Spain also filled up with mysterious German “businessmen” seeking out this precious metal.

Hitler’s payments to the Bank of Spain were received regularly and on time in the form of ingots with a swastika engraved on each one.

Chemistry and espionage

The Allies knew that the tungsten that was maintaining the Nazi war industry was almost exclusively sourced from Spain.

And for that reason, Galicia filled up with spies.

On the one hand, many Germans relocated there to manage the mining and transport processes while Nazi submarines operated in Galician estuaries with complete normality. The Germans even built the Valarés harbour in Ponteceso to facilitate easier tungsten cargo loading (decades later this harbour would be reused by tobacco smugglers).

Meanwhile, on the other side, British and American spies tried to prevent these operations from being carried out by any means necessary.

The situation became even more tense at the end of 1943 when the Allies began to prepare the Normandy landings.

One of the elements that was vital to the success of the operation was to weaken the powerful German war industry.

That caused increased Allied pressure on Franco (who theoretically was neutral).

Ultimately, it was the sales embargo on petroleum destined for Spain that truly led Franco to reduce the sale of tungsten to Germany.

In fact, it was the inability to guarantee an energy supply —together with the threat of invasion from the British and Americans— that made Franco change his mind, thereby drastically reducing tungsten sales to Germany.

The subsequent Allied military advances, and increasingly smaller amounts of available tungsten, were decisive in the final defeat of Nazism.

This year, 2020, will be the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, yet the strategic importance of tungsten hasn’t wavered a bit.

Even today, large world powers like the United States maintain strategic reserves of the chemical element, enough to guarantee a six-month supply.